Are NFT Projects Appropriating Cultures?

Some are now accusing NFT artists and entrepreneurs of cultural appropriation. One such area is in New Zealand where Maori artists complain

Since NFTs earned global popularity, there have been reports of IP thefts and cultural appropriation; this piece will look into the realities of cultural appropriation in the age of NFTs.

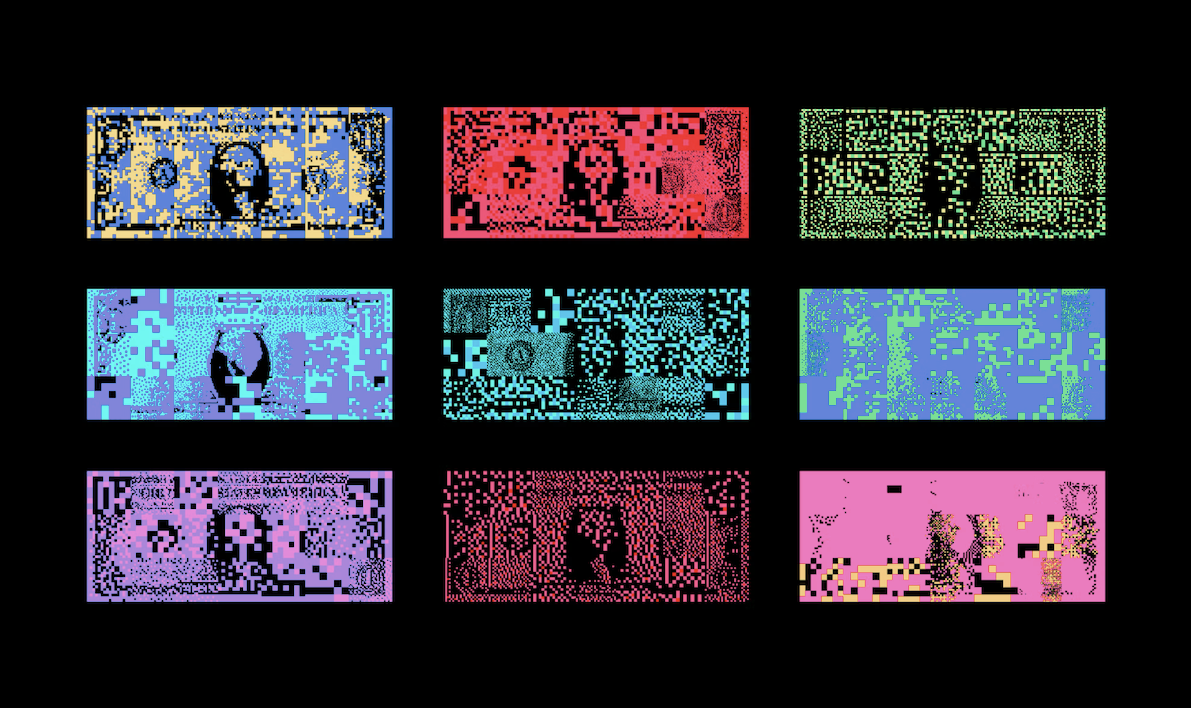

Culture is the new currency

Few topics are more sensitive than culture; when we talk about culture in the sense of European colonialism and expansionism, it’s bound to hit a nerve. For too long vulnerable cultures across Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania have been at the whim of global powers.

In arts and entertainment, cultural appropriation was one of the most used buzzwords in the 2010s. Cultural appropriation is when a person or organization from a culture, ethnicity, race, or other identifying elements profits off different cultures without fair compensation, carrying members of the appropriated cultures along or acknowledgement.

Live in a country where you are considered part of a “minority” group. You may understand what it feels like when people and organizations in the “majority” pick parts of your culture they think is cool and earn off it without compensation or support for the appropriated cultures.

Cultural appropriation continues to be a problem in the art world, and it seems to have made its way to the NFT space. Unlike stolen IPs, there are few surefire ways for platforms to decide what is appropriated and what isn’t. There aren’t precedents for punishing people who sell NFTs that may have elements of other cultures in most cases.

NFT Cultural Appropriation: taonga Māori case study

Today, we’ll look into how recent NFT projects may be peddling false stereotypes about Maori people in Oceania. During European exploration, explorers viewed Māori and related tribes as savages, barbarians, and violent warriors during the early days. In more ways than one, this falsehood spread into popular culture, arts, and now NFTs.

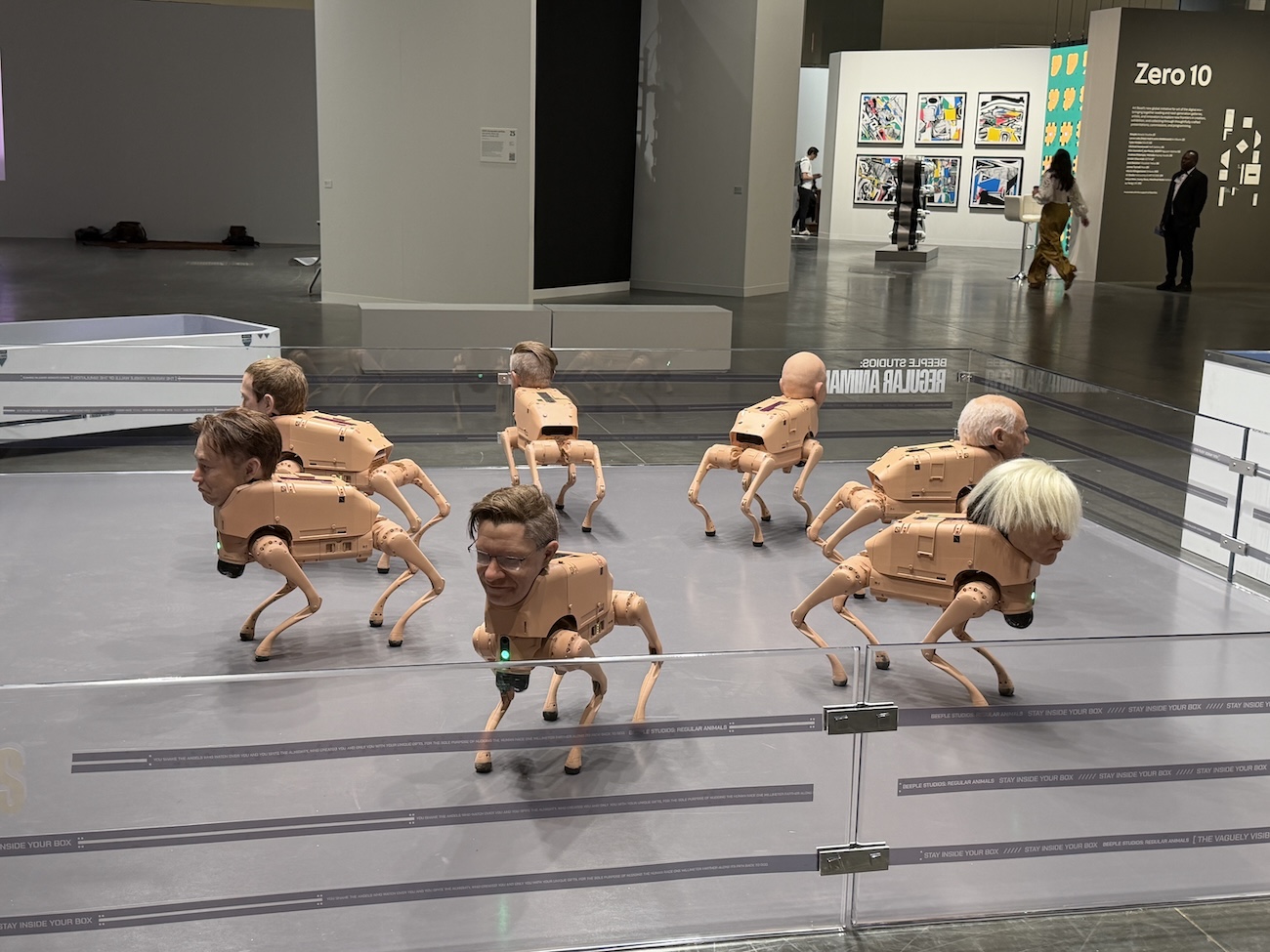

Karaitiana Taiuru, an intellectual property cultural adviser, had the following to say concerning the appropriation of Maori culture in NFTs. “I’m already seeing a number of images of ancestors that are from publications being used and manipulated. There are faces on top of someone else’s body [and] moko from the face being added to other peoples’ faces. They’re inappropriate images, and they’re degrading Māori culture.”

Rawithiroa Bosch, a Māori photographer, was appalled by how the culture was misappropriated on OpenSea when he tried to convert some of his works to NFTs. “Literally people getting Google images of a pou whakairo or a mere or a tewhatewha, putting it on OpenSea, and selling it as an NFT. Someone that is ignorant to that would go, ‘oh, this is a Māori thing, OK, I’ll buy that.”

How can the community stop misappropriation of cultures?

The primary problem with cultural appropriation isn’t the usage of cultural elements without permission; it’s the fact that many people use aspects of a culture that are untrue (without knowing better), thereby spreading stereotypes that can be harmful.

Some Māori NFT creators have floated the idea of having some quality assurance or authenticity stamp on Maori related artworks and NFTs created by Māori people.